Remembering Pacific Overtures

Composer-lyricist Stephen Sondheim, particularly when he was paired with director Harold Prince, moved and shaped musical through bold experiments that challenged audiences while unearthing new possibilities. The musicals that this duo together brought to the stage included Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd and Merrily We Roll Along. Each was innovative in its own way, redefining the Broadway musical as we knew it. There was one other show that they created during this decade (and change) which may have been the most challenging (for audiences), clever (by even Sondheim and Prince standards) and groundbreaking (for posterity) in terms of the possibilities it demonstrated. That musical was the short-lived 1976 Pacific Overtures, which would also employ book writer John Weidman as part of the collaboration.

To begin, Pacific Overtures was to tell the story of the westernization of Japan, from 1853 and the arrival of the Americans as part of Admiral Perry’s expedition which took the country from a policy of isolation to being an important crossroads of international trade routes. The musical is told from the point of view of the Japanese, as they experience their culture, traditions, and very lives jeopardized, encroached upon, and ultimately altered by western influence. The Japanese, who had remained mostly removed from world politics and commanding no navy of their own, were not prepared when Perry arrived (with large gunboats). It was obvious the Americans were planning on taking their country by force if necessary. Since they had no viable options for recourse, the Japanese had no other option than to concede to Perry’s demands. Pacific Overtures would demonstrate the story of how one country, steeped in tradition, would suddenly find itself thrust into the modern world, whether it wanted to or not.

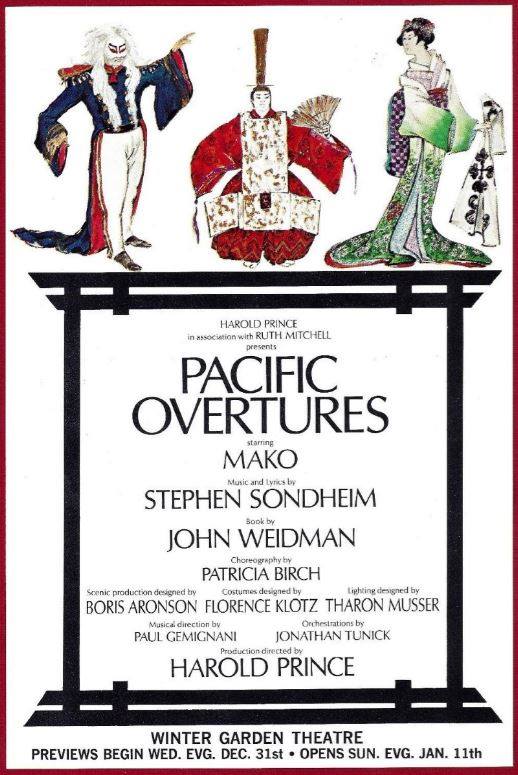

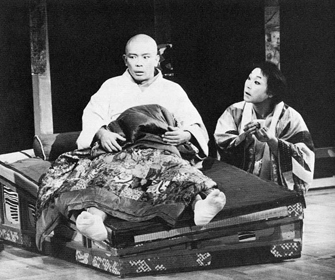

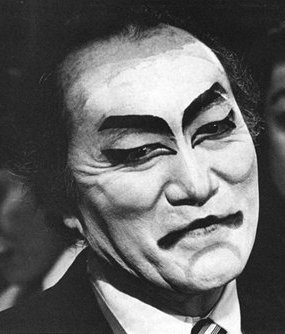

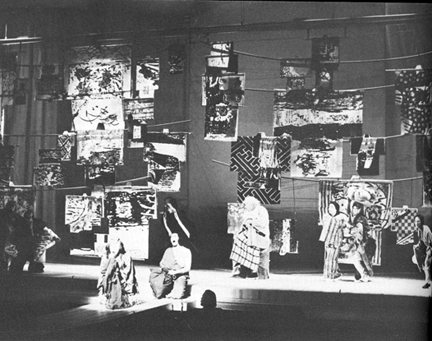

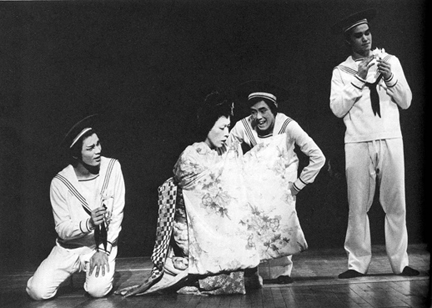

For some, this might not sound like a particularly exciting night of musical theatre. For those who were used to shows like Hello, Dolly!, Promises, Promises, or even the more experimental Company, Pacific Overtures was a major departure from what they were used to. Sondheim, ambitious as ever, set out to write a score that would sound Japanese. He did not use the pentatonic scale (traditional of much Asian music), but employed parallel fourths and no leading tone to give a similar effect. Director Harold Prince would stage the production in a style of Kabuki Theatre, with men playing all the female roles and set changes made in full view of the audience.

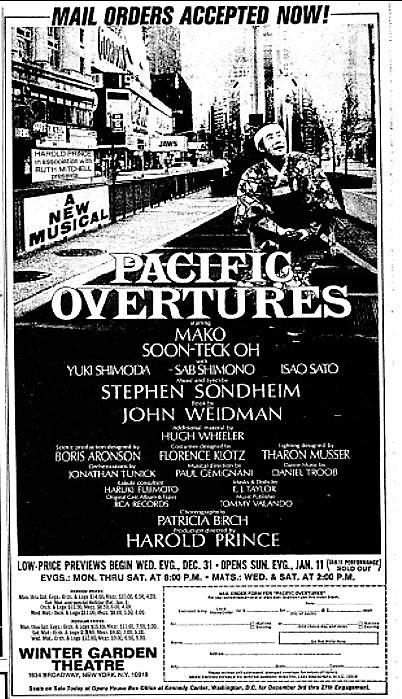

Casting Pacific Overtures would prove to be one of the greatest challenges of assembling the musical. In 1976, the pool of male, Asian actors of a Broadway caliber talent was small, or at least hard to locate. Broadway rarely had opportunities for this ethnic minority. Still, the talent was ultimately found and a cast starring Mako, Soon-Tek Oh, Isao Sato, Yuki Shimoda, Sab Shimono, Ernest Abuba, James Dybas, Timm Fujii, Haruki Fujimoto, Larry Hama, Ernest Harada, Alvin Ing, Patrick Kinser-Lau, Jae Woo Lee, Freddy Mao, Tom Matsusaka, Freda Foh Shen, Mark Hsu Syers, Ricardo Tobia, Gedde Watanabe, Conrad Yama and Fusako Yoshida, was assembled.

Pacific Overtures is best described as a concept musical that explores perspective as it relates to history. Sondheim and Weidman wrote a story that asked audiences to forget history as we had been taught it and to look at it through the fresh eyes of a different culture, those who experienced history as it happened to them, ushered-in by Americans against their will. But the show wasn’t just that. Pacific Overtures also looked at history from the perspectives of seeing it verses hearing it, experiencing it as a child and remembering it as an adult. This is gloriously studied in Sondheim’s brilliant set-piece “Someone in a Tree” which offers all of these viewpoints on one little piece of history. History is subjective. History is an agreed upon collection and recollection of events. Seldom is it ever entirely accurate.

Pacific Overtures opened at Broadway’s Winter Garden Theatre on January 11, 1976 where it ran for 193 performances. Audiences and critics were starkly divided over the show. Some felt it a tedious evening, a cerebral history lesson and a musical theatre experiment gone wrong at the expense of the ticket buyer. Yet, there was a faction of ticket buyers who thought it an innovative, breathtaking. musical theatre experience, reveling in how Prince, Sondheim and company incorporated conventions of Asian music, theatre and culture into the show. Many were in awe of Boris Aronson’s set and Florence Klotz’ costumes, the only two Tony wins the production would receive (it was the season of A Chorus Line, after all). The patient and reflective theatergoer, however, understood that this experiment in musical theatre was special, even groundbreaking, and they walked away fromPacific Overtures with their hearts and minds bursting as they considered musical theatre’s potential and its possibilities.

Mark Robinson is the author of the two-volume encyclopedia The World of Musicals, The Disney Song Encyclopedia, and The Encyclopedia of Television Theme Songs. His forthcoming book, Sitcommentary: The Television Comedies That Changed America,will hit the shelves in October, 2019. Hemaintains a theater and entertainment blog at markrobinsonwrites.com.